Early internet subcultures used to be a haven for individualists and techies. But social media has become a hotbed for groupthink and reactionary cults. Surprisingly, many of these communities are comprised of the same people. From New Atheist to TradCath; how 2013’s seasteading programmers became 2019’s blood-and-soil peasants.

In the past few years there has been a radical transformation within internet subcultures. For many of us who grew up online – as nerds, gamers, or introverted creatives – the internet was a place you could go to “be a loser with your friends”. Before Web 2.0, fandoms and message boards were something of a safe space for the IRL socially awkward. But today’s internet is overrun by social media, set to the ever-accelerating pace of technocapitalism.

2013: Sandbox Rationality

Sandwiched between hours of gaming and anime porn, contrarian teenagers embraced the position of the enlightened outsider or the rational sceptic. In a society filled with conflicting narratives and suspect institutions, atomised individuals are drawn to simple explanations they can see and confirm with their own eyes.

Anarcho-capitalism is the “flat earth” of political theory. Ancap is a radical form of right-wing libertarianism that reduces politics to a single fundamental axiom. The “Non-Aggression Principle” states that “No one may threaten or commit violence against another man’s person or property.” In the vacuum of the internet, isolated young men attempting to build a worldview from scratch were intractably drawn to this idea.

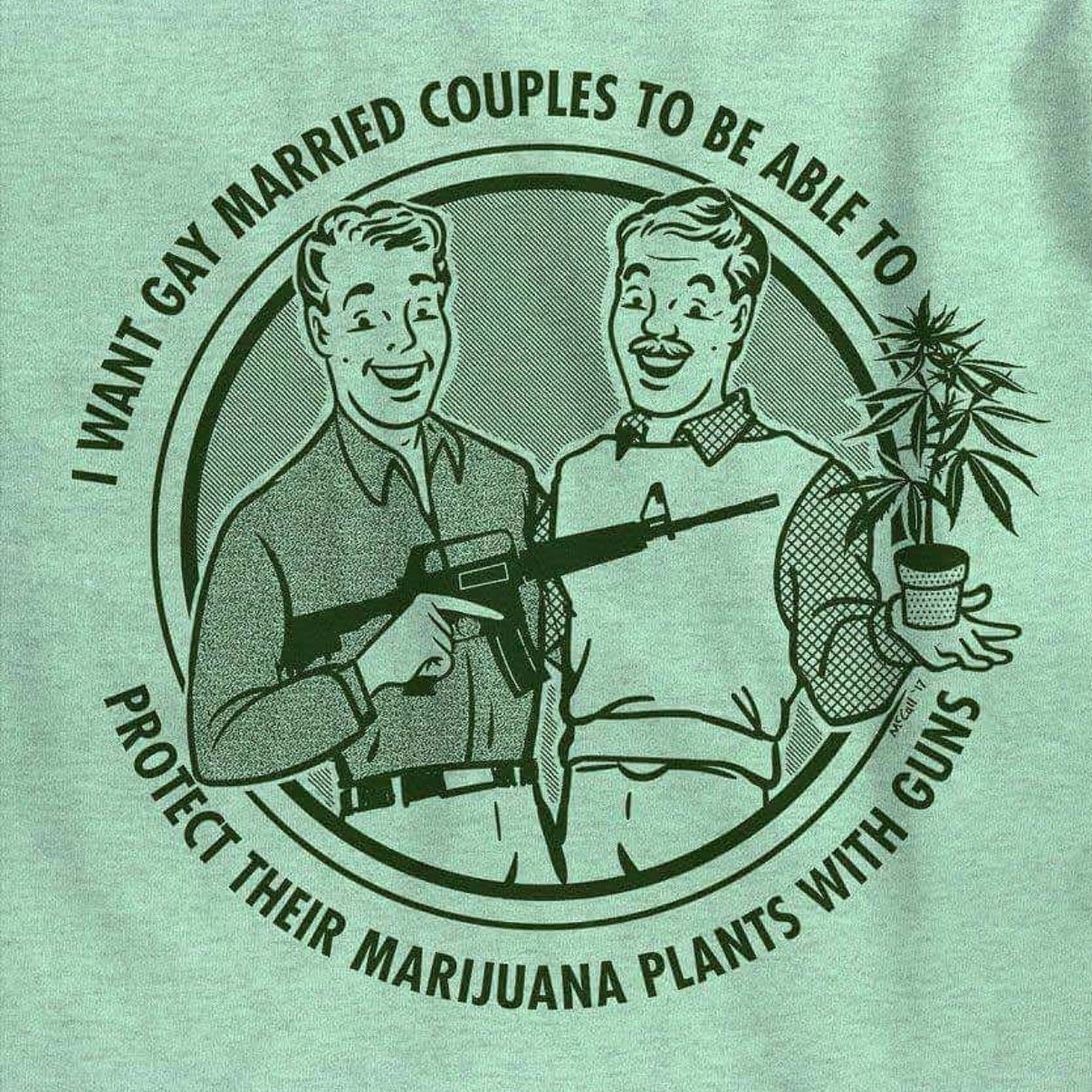

The meme goes something like this: “I want gay married couples to protect their marijuana plants with unregistered firearms they bought with Bitcoin.” Cyberspace was a place for freedom. The ancaps always made it clear that their opposition to welfare wasn’t about race; it was about giving money to people who hadn’t earned it by taking it from those who had. “Taxation is theft.” Charity is encouraged but wealth redistribution is a violation of the NAP. The uniquely American mythology of homesteading laid fertile groundwork for a worldview organized around property rights.

The nerd-CEOs of Silicon Valley had become mainstream celebrities. Once unshackled from the oppressive institutions of the state, the ancaps believed that they too would become Randian heroes. In December 2013, Bitcoin exploded to first reach a record-breaking value of $1,000. It felt like everything the early tech-evangelists had foretold was suddenly now real in a way that was impossible to ignore.

2016: “Water the Tree of Liberty with Blood”

As online libertarians rushed to defend the free speech of edgy influencers, they also happened to listen to a lot of what those provocateurs had to say. To an audience of mostly young white men, it didn’t sound like these figures were saying anything untrue. Many accounts began posting politically incorrect memes to lampoon and expose the illiberal hypocrisies of censorious campus progressives. Early attempts at deplatforming confirmed that free speech was indeed under attack online. Soon, the increased strain of political division caused codified echo chambers to algorithmically snap into place and further polarize the social-media landscape.

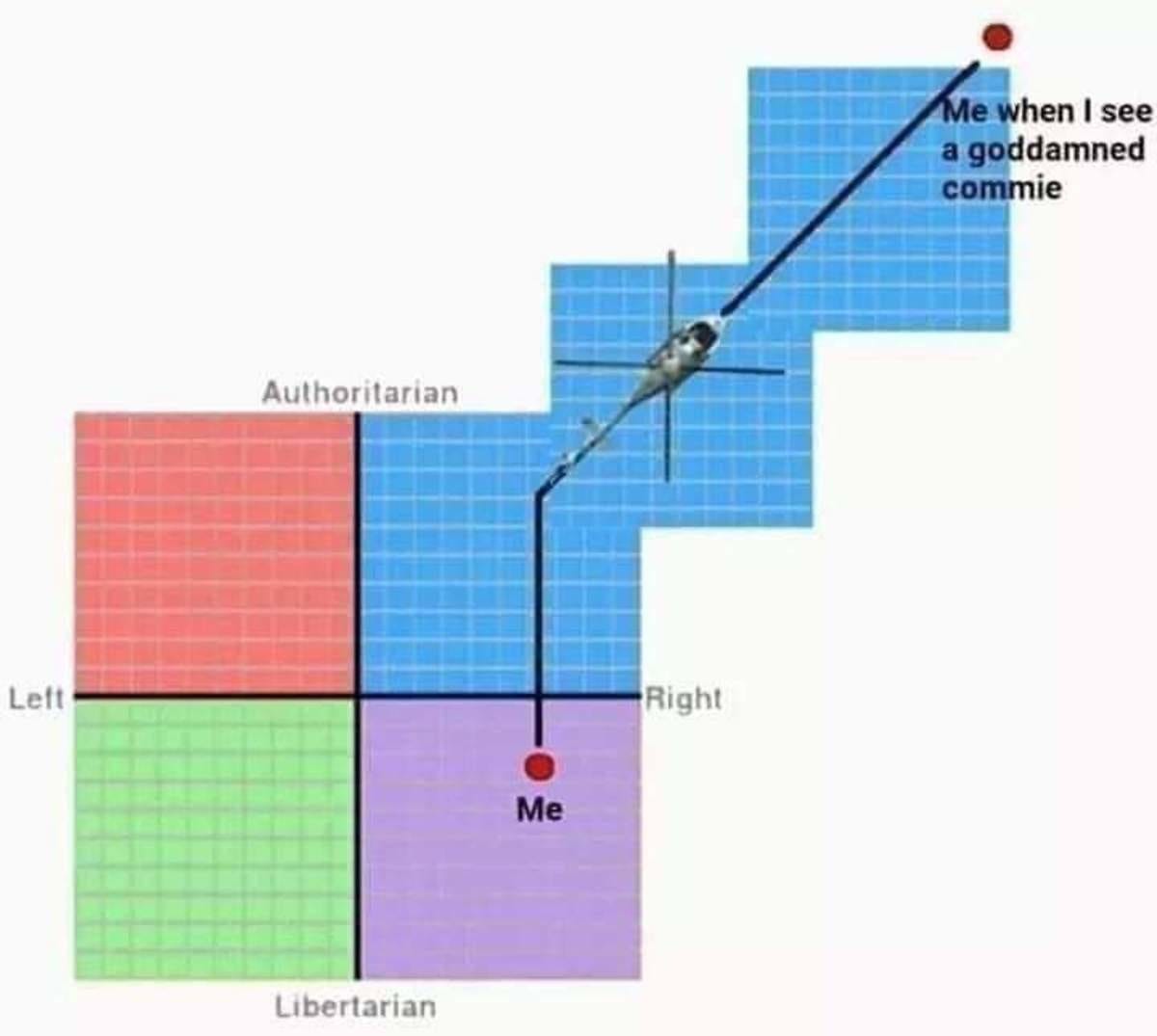

This newly perceived attack from a “left-wing” establishment caused many ancaps to reconsider their commitment to non-aggression. Social media soon overflowed with memes depicting radical libertarian thinker Hans-Hermann Hoppe, neoliberal dictator Augusto Pinochet, and, of course, Pepe the Frog. To preserve their precious libertarian freedoms these users opted to temporarily embrace a centralized authority until the threat had been “physically removed, so to speak”. This path of radicalization – from ancap to civic nationalist – became so common that it grew into a meme itself.

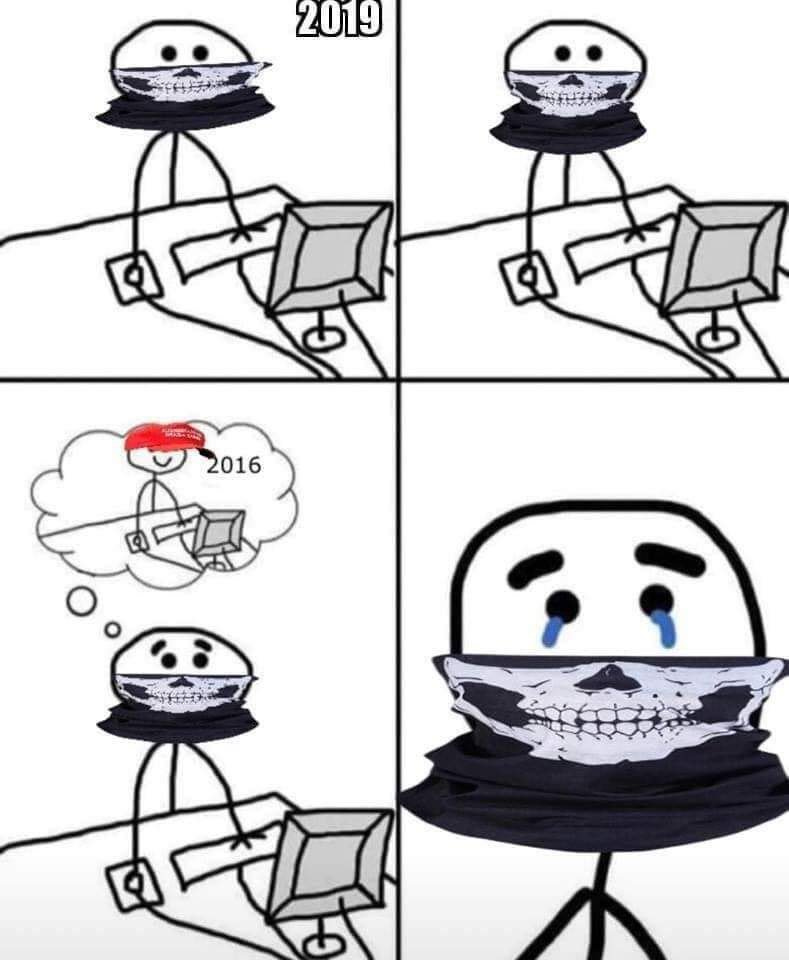

The outcome of 2016 US election took even the shitposting accounts by surprise. They gave each other “medals of honour” for their service in the great meme war. Being on the winning side encouraged these online participants to push the culture wars even further. Right-wing influencers worked to stoke racist sentiments and platform ideas that many libertarians had held privately but never publicly expressed. As violence erupted in the streets, those who were there “for the lulz” finally called it quits, but many others doubled down and abandoned the irony that had originally brought them there.

2019: Accelerate the Collapse

The Trump administration’s failure to deliver on its more radical rhetoric slowly caused far-right enthusiasm to fade. Without a unifying symbol, the alt-right splintered into factional disputes and infighting. The Randian heroes of Silicon Valley had similarly fallen out of favour. Their explicit support for progressive Democrats, combined with the ongoing threat of deplatforming, made it clear that these tech-industry titans were part of the very establishment that online subcultures were actively fighting against. Getting “Zucked”, aka banned, became a badge of honour. Pornography was out and religion was back in a big way. The New Atheists and fedora-toting pickup artists of a few years ago had become the Trad Caths and accelerationist reactionaries of today.

The most significant change that took place in these communities was, however, a reversal on the perceived freedoms of capitalism. Right-wing influencers made it clear that the very concept of libertarianism was itself historically and intrinsically “white”. The freedoms that these teenagers had inarticulately described in their youth were in fact dependent on the traditional values of western civilization. Soon, capitalism was understood as a process of deterritorialization, eroding the time-tested social structures that allowed for the naive concept of “liberty” in the first place. Having bypassed neoconservatism on their path to radicalization, climate denial was never really part of the rhetoric and now imminent environmental catastrophe gave a new sense of urgency to their more radical demands.

The memes that circulate in these new online circles retain their familiar aesthetic forms but can no longer be described as jokes. They are not images intended to attract a new audience through humor. Instead, they work to reinforce the views of those who are already radicalized and in the movement. These accounts routinely upload violent video footage set to epic inspirational music or composited into first-person shooter games. The atomizing processes of social media have become a well-oiled machine for churning out decentralized lone-wolf acts of terror.

Mapping The Funnel

While this multi-year arc may sound absurd to outsiders, it forms an extremely common path to radicalization. This process has been called the “libertarian to alt-right pipeline”, the “anti-SJW rabbit hole”, the Pewdie-Pipeline, sometimes the “dark enlightenment”, the “alt-right funnel”, and many other names. To some degree, this demonstrates what viral movement-building looks like in a post-platform society: cross pollination between nodes within a distributed network that collectively work to refine a message and slowly convert viewers from tacit to active supporters. The early links in the chain have little awareness of what they are involved in, but their communities make fertile hunting grounds for people with more radical ideas.

The libertarians of 2013 were at least rhetorically tolerant: they would battle mainstream conservatives in the comment threads to defend gay rights, decry racism, and advocate for personal freedoms. Any disparaging generalization about a group was seen as an attack on the personal sovereignty of those members as individuals. Property rights, and ultimately self-ownership, are sacred within the libertarian worldview. Unfortunately for the libertarian teens of the 2010’s, history did not allocate most members of society any form of property whatsoever. Primitive accumulation did not abide by the NAP. As a result, most people under capitalism are coerced into selling their labor power just to survive.

Rather than backtrack on their faulty sandbox assumptions, 2016’s right-wing influencers, combined with the inflammatory and oppositional structures of social media, encouraged these young people to double down on a complex maze of nested ideological positions: property rights within civic responsibility within a loosely defined concept of “the west”. The internet subcultures of 2013 were free-market evangelists, rhetorically equitable but racist in practice. The internet subcultures of 2019 are explicitly racist but demand market regulation.

The formation of the “new right”, or really the old right that is now online, in some ways sets the narrative of social media since its widespread adoption. As fewer people are able to access the benefits of the mainstream, citizens move towards further polarized edges of the political spectrum. The deep reactionary forces that emerged in the last decade will undoubtedly haunt the future of mainstream politics for years to come. The question remains whether these online spaces can be harnessed towards a progressive and emancipatory movement of the left.

***

I originally wrote this piece back in 2019 for Spike Art Magazine. It was only available in-print or behind a paywall. In the years following, the media narratives and academic research around these topics has been disappointing and at times detrimental. I think we need better, more honest narrators to engage in the public discussion. I’ll be republishing a lot of my work that was previously only available to niche circles and putting it online for free.

Spot on. This is an almost perfect continuation of where Angela Nagle’s “Kill All Normie” left off.