Doomscroll guests:

and are now on Substack. These are two of my favorite writers — keep a close eye on what they get up to.Listen to the audio version of today’s newsletter:

I recently spoke with documentary filmmaker and host of Channel 5, Andrew Callaghan on Doomscroll #19. In the episode, we discuss “Andrew’s Theory of Radicalization” which he outlines in the introduction of his new film Dear Kelly (2025). Briefly summarized, Callaghan argues that political radicalization occurs when individuals lose access to three core needs:

Security — material safety such as the home and other necessary goods for survival like food and energy

Significance — the ability to participate in meaningful work that gives us a sense of purpose in society at large

Connection — strong social bonds that create a sense of belonging such as family or in-person community ties

During our conversation, I mention my own theory of radicalization that I will describe in more detail in today’s newsletter. If you value these discussions and want to support this project, you can become a paid subscriber and get access to all bonus episodes of Doomscroll, My Political Journey and more:

Radical Content

In recent years, media coverage has focused on the unintended consequences of algorithmic recommendation and ignored the socioeconomic drivers that cause people to seek out political content online. Radical messaging has existed across all eras and forms of media but it relies on real political crises to find a receptive audience.

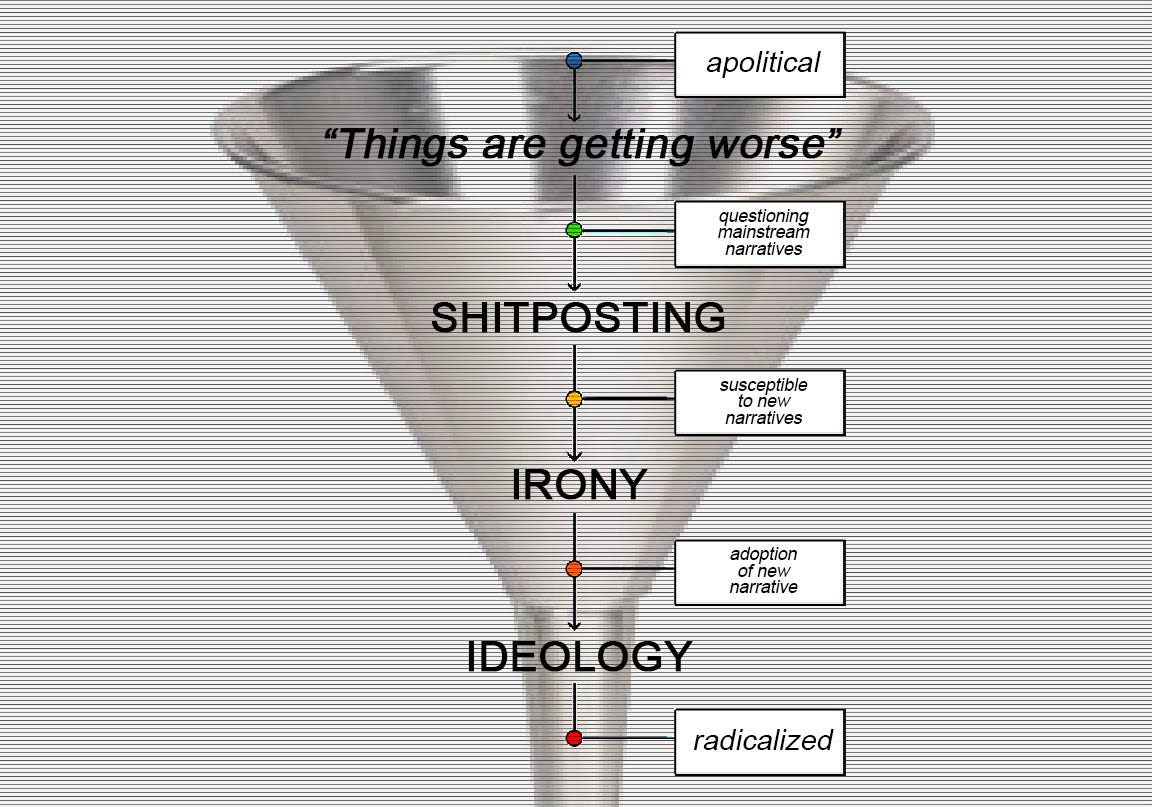

Radicalization is often described through the metaphor of a funnel — an informal network of diffuse messaging that is spread out over time and across channels. Viewers will often begin at large mainstream programs and, over the course of several years, move through successive channels as they descend into more isolated or extreme views. As they dive deeper into radical content, the broad reach of this messaging is refined into a more niche ideological worldview that primes viewers for political action and recruitment.

The metaphor of ‘the funnel’ draws on two key sources. Primarily, it refers to marketing diagrams that measure the reach of advertising media, click through rates and eventual sales. These comparisons of reach and conversion rates help to measure the effectiveness of a certain campaign, slogan or idea. In the advertising industry this ratio is commonly referred to as “eyes to buys”. Secondly, the metaphor of the funnel is borrowed from the field of counter-terrorism, in which researchers attempted to map and generate predictive models for radical Islamic attacks during the Global War on Terror. In these studies, researchers would measure the reach of radical media from extremist groups and attempt to narrow down what portion of that audience was a risk for committing real world violence. In the example of extreme political groups broadcasting over YouTube or other platforms, this dual application of the funnel became a useful and largely accurate way to describe the phenomena of online extremism.

One notable study in this field is Alternative Influence, authored by Becca Lewis and published by Data & Society in 2018. Lewis maps the process of online far right radicalization on YouTube. These familiar content pathways became known as “pipelines” in popular media and commentary.

Funnels and pipelines form the basis of our analysis for online politicization. Funnels refer to the broad reach of media messaging. Pipelines describe the most common pathways through these networks. In the past few years, much of my work has been an exploration into these phenomena and a proposal for how these processes could be utilized toward more progressive ends.

At the top of the funnel one can find popular channels with varied content and low conversion rates. Going further “down the rabbit hole” means encountering more niche or politically radical content; overall view numbers go down but conversion rates go up. As viewers descend into the deepest levels, they can discover more extreme views. Radicalization is a process of clarifying ideological inconsistencies and it requires that viewers are slowly acculturated to extreme ideas over time.

Importantly, these funnel and pipeline analogies suggest that belief systems are always in motion. In an era of hyper-polarization, it is necessary to underline that viewers can in fact be persuaded. No worldview is ever truly set in stone.

Josh’s Theory of Radicalization

Online radicalization is the result of three key factors:

Economic Precarity — Americans are working harder for less.

Most people in the United States are downwardly mobile and life expectancy is steadily declining. These material factors help drive individuals out onto the internet in search of new narratives to explain the world around them. The root cause of radicalization begins at our material conditions.

Social Atomization — Our circles of trust are getting smaller.

Community bonds used to serve as a levee against excessively radical politics. There are degrees of material immiseration that can be withstood by the comfort of social connection and its informal networks of material support; preferential access to jobs, pooling resources like child care or even local charity. Studies indicate that the average American’s number of close friends declines with each subsequent generation. Many Gen Z’s have 1 or 0 close friends.

Content Consumption — And we’re watching more than ever.

The attention economy of online media further incentivizes polarization. While it is important to acknowledge platform design as a contributing factor, it should not be mistaken as the root cause.

Over the past decade, major platforms have attempted to redesign their algorithms or to expand censorship and demonetization policies. In 2019, YouTube boasted a 70% reduction in view times on radical content. However, these mounting trends continue to rise across all of our society. Each year, a growing number of people head out onto the web in search of coping strategies, social connections and political solutions.

Regardless of how we tune our algorithms or platforms, these offline material conditions will continue. Better algorithmic recommendations may help to slow the speed of radicalization but it cannot reduce the accumulated pressure of American life. Referring back to the funnel analogy, the flow rate remains the same.

When analyzing the impact of online messaging from various political groups, we are faced with a categorical question — are these media channels or political organizations? As we explored in a recent post, Podcaster Politics:

Under the current design of our communication networks, cultural commentary such as sports, video games or comedy, is structurally indistinguishable from channels that focus on social issues or even those that belong to official political organizations.

Today, all political organizations are also media channels and vice versa. In this new paradigm, the only metric that matters is conversion rates: what channel can place a call to action that mobilizes that largest portion of their audience? Who has the highest ratio of “eyes to buys”.

As viewers descend deeper down the funnel, view numbers go down but conversion rates go up. This process resolves when a channel’s click-through-rate reaches 1.0. At this level, every listener is a supporter and could be considered a member of a nascent form of political organization. These highly dedicated groups can coordinate to turn out members at protests or other political actions. (It already costs more to support a podcast than it does to become an annual dues paying member of the DSA.)

Media channels and official organizations are becoming more structurally similar. Like radical newspapers of the past, they are collecting new audiences that can be mobilized toward political goals.

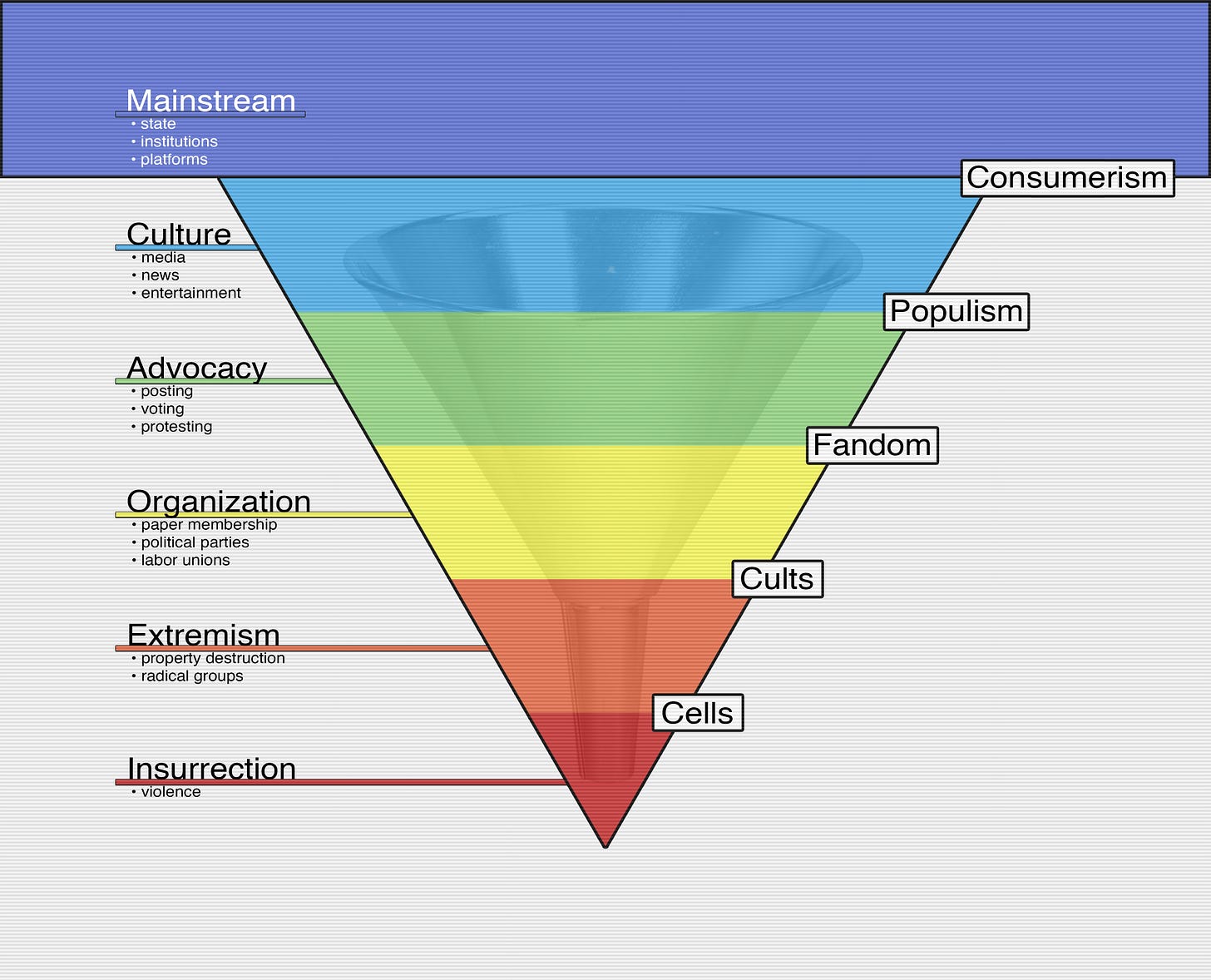

In this new gradient of alt-media and politics, we can roughly classify different stages or tiers of reach. Each category grows smaller in size but becomes more dedicated and isolated in its beliefs.

Consumerism — presence on entertainment media, mainstream news media and all major platforms. These narratives are part of pop history.

Populism — presence on mainstream news media and all major platforms. These narratives emphasize lesser known histories.

Fandom — presence on major platforms and some alt-platforms. These narratives describe an alt-history; the popular record is incomplete.

Cults — presence on some major platforms and alt-platforms. These narratives describe a counter-history; the truth has been hidden.

Cells — presence on alt-platforms and self-hosted back-ups. These narratives are more akin to lore and may not align with outside evidence.

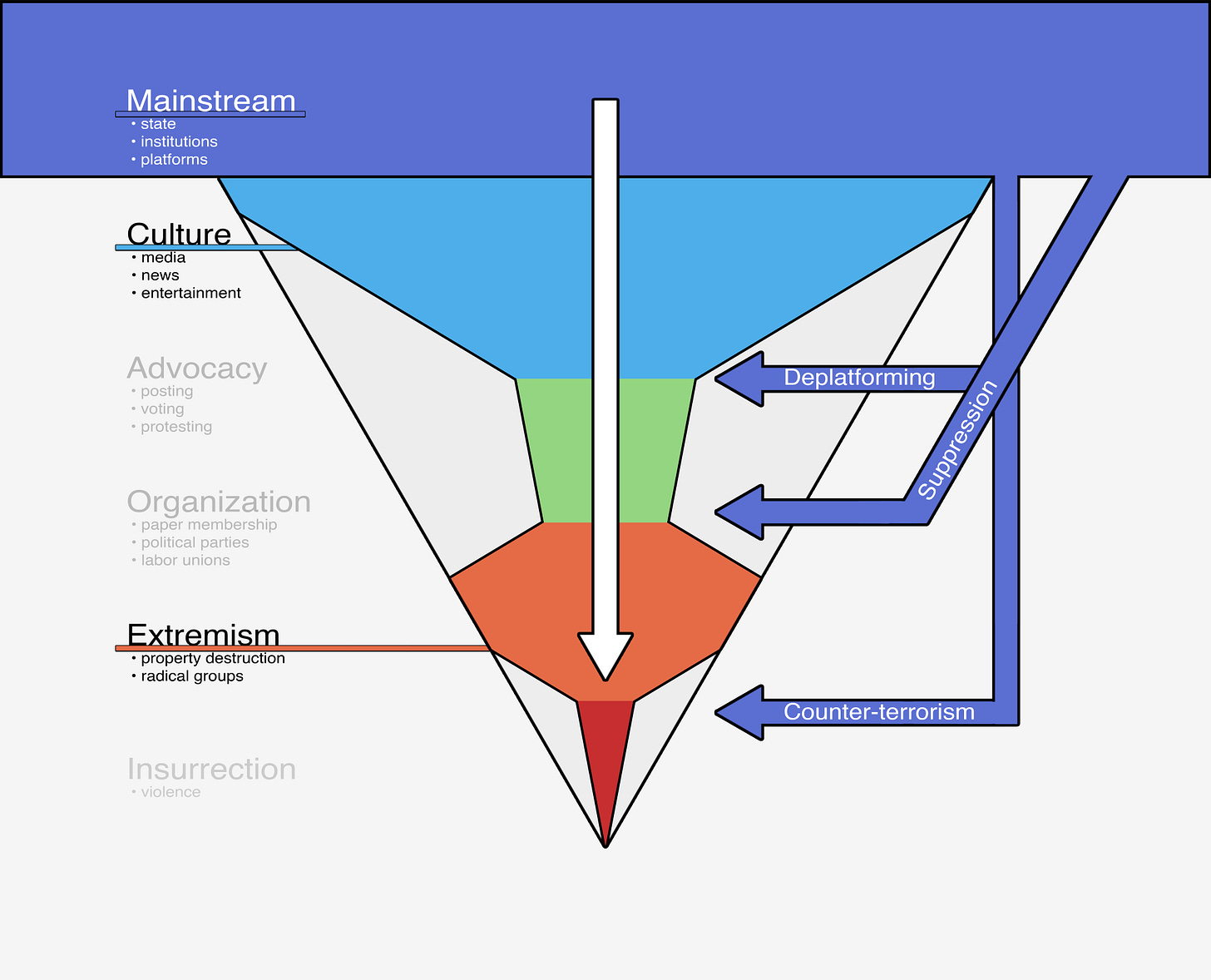

These abstract categories and theories are useful in conceptualizing the role of radical media and its political impact. But the real world outcomes are also shaped by interventions on behalf platforms and state actors that can distort, slow or even accelerate this process. Visualizing today’s political media environment might look something more like this:

In the United States, most political organizations have long since withered, dissolved or been suppressed. During the post-political era, we saw many informal organizations and disorganized protests. Today, the desire for proper organizations has largely been replaced by online communities focused around radical media. The task ahead of us is to recognize this process and seek ways to rebuild political organizations out of our current media environment.

Belief systems are in motion and politicization is a process. In these abstract theories and diagrams, we could consider each tier as a layer of resistance which slows the progression into deeper levels. But today, socioeconomic drivers are increasing and young radicals will often pass directly from the layer of Culture into Extremism — because we have no organizations left to join.

American political life has become a highly pressurized bottleneck where the lack of real political organizations rapidly propels people through successive stages of radicalization. Once young radicals conclude that there is no effective means of political change, extremist measures may appear as a logical next step.

Cult as Cope

Today, social media feels like standing in the cereal aisle and trying to choose from 1,000 different flavors of narrative. Algorithmic recommendation has lost consumer confidence but there is still too much information to parse. In an era where legacy institutions have become transparently corrupt, choice paralysis is driving media consumers towards independent editorial voices. In the absence of real organizations, listener funded counter hegemonic narrators are thriving. The alt-political influencer doesn’t report — they just interpret the news for you.

But as our overall prospects dim, there is less use in having the correct interpretation. Here, the secondary role of the influencer-as-cult-leader becomes dominant. I can't separate the signal from the noise. So just tell me what to think. Honestly, I’m relieved that I no longer have to choose. Small pockets of consensus reality can help to create a sense of meaning and fulfillment when larger material changes are deemed to be impossible.

Ahead of us lay two possible futures. On the first path, we may rebuild the organizational layer of American political life. This is a multi-generational project but not a hopeless one. Its progress can be measured over time. On the second path, society may fracture into increasingly nichified pseudo-cults that are exponentially carried off by the long tail of social media networks. In this case, new cultures of evolved rituals and lore will serve as coping strategies as we sink deeper into decline.

Much of this material is drawn from a report I published in January of 2021 titled Radical Content. Radical Content was designed as an easily distributable trend report that gave context to the radicalization debates at the time. There is no technical solution for a political problem.

Andrew Callaghan is one of the few independent voices that has similarly engaged in a deep exploration of online political subcultures and primary sources. His work allows us to see all the rage and frustration of American life, exhibited by subjects who do not have a theory of class struggle or a plan for how to fix it. The task for the left is to recognize the root cause of these grievances and to funnel this anger toward more productive ends.

On this week’s private episode, we discuss our insights and experiences in the field, including the ethical decisions and personal challenges that come along with it. If you prefer these longer format ~1 hour bonus episodes, this is a good chance to show your support and become a paid subscriber. I’m still experimenting with the episode length and style for the show. I think this discussion with Andrew strikes a tone and balance that feels true to us:

Supporters get access to the full archive of bonus episodes:

"In the absence of real organizations, listener funded counter hegemonic narrators are thriving. The alt-political influencer doesn’t report — they just interpret the news for you."

That's why I exclusively read Joshua Citarella's Newsletter - the alt-political influencer and counter hegemonic narrator in the business of discussing the counter hegemonic narration of alt-political influencers.

Jokes aside, thank you for this piece and your work, Josh!

"Radicalization is a process of clarifying ideological inconsistencies and it requires that viewers are slowly acculturated to extreme ideas over time."

Really on point. Radicalizing is about embracing the new narrative, but in order to do that (seeming) inconsistencies must be addressed. People don't roll into a narrative as a blank slate. They come into a new narrative with a whole lot of baggage. Particularly if the society has made a strong effort to immunize the person against another narrative (for example, anti-communist propaganda in the US). Whether these inconsistencies are real or fabricated depends on the flavor of extremism (or who you ask).

Only thing I would add, is that besides the pressure points suppressing certain parts of the funnels, there is also a release of places where pressure used to exist that has dissipated, inducing radicalization. Like lacking community or atomization causing a lack of narrative pull towards the mainstream.

Historically, many people have gone through tough times without radically changing their narrative. In part because there were no alternative narratives readily available, but also because there was still a strong ideological pull from the tight, very local, communities people belonged to.