TrueAnon #425: The Blue Light Killer. I recently sat down with my favorite internet sleuths for a 3 hour episode diving deep into Luigi Mangione’s political ideology. We explore his possible motivations for killing UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. Most of the media coverage has treated this story very superficially. I think we do a good job of getting to the roots of his complex techno-accelerationist worldview. Episode is out now.

Friendly reminder, this is a reader-supported newsletter. If you think this work is valuable, you can buy me a cup of coffee this morning. Subscribing for the full year gets you a discount and helps me to plan long term projects like Doomscroll:

Doomscroll is now available in audio form on Apple Podcasts + Spotify + everywhere else. Audio episodes are coming out every week.

“The biggest red pill is just reality itself” — this is one of the most potent lines from any interview I’ve done. More than any meme or idea that one might encounter online, the day to day experience of reality is causing people to become radicalized.

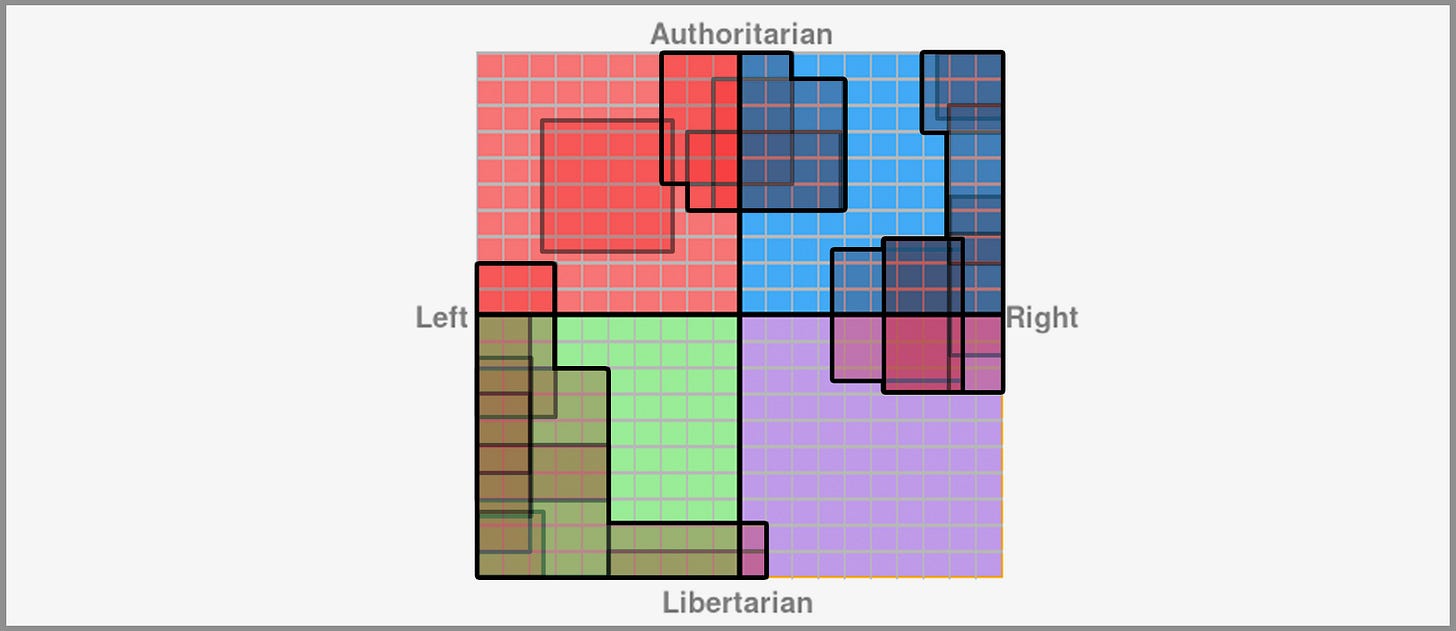

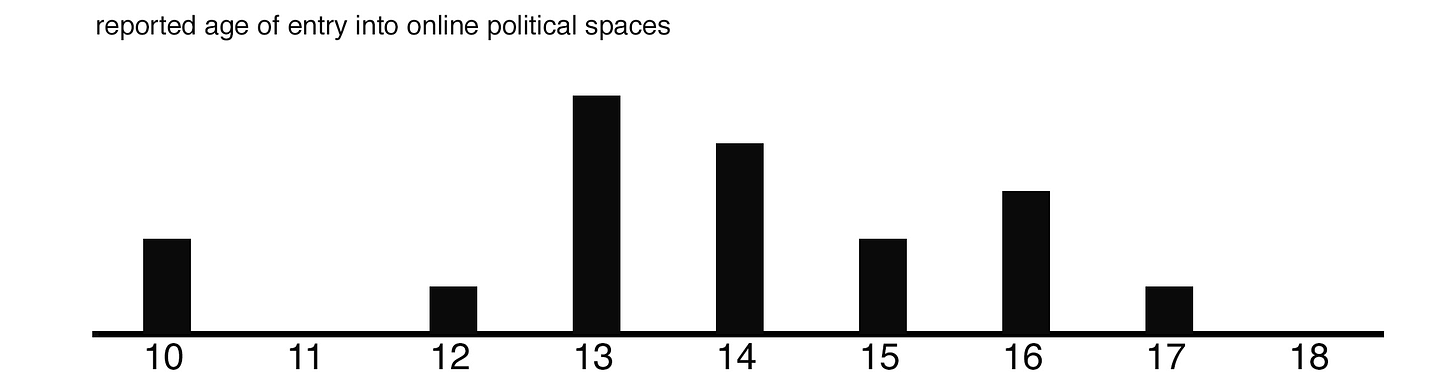

If you’ve been following this newsletter since the beginning, you will know that I spent several years interviewing Gen Z meme posters from across the political spectrum. This is the last installment of a series titled 20 Interviews. For this project, I spoke with young people ages 15 - 22, half of whom were from the left and the other half from the right.

20 Interviews and My Political Journey are deeply personal, qualitative interviews with young people who have been politicized online. My unique role as an artist allowed my interview subjects to trust me. Most of these subjects would have been skeptical of mainstream journalists or just refused to talk to them at all. Few writers have had the interest to meaningfully explore this space. Those who do engage with it are rarely able to get access to the anonymous posters who shape so much of today’s online culture and discourse.

In most cases, I deeply disagreed with the views of my subjects but withheld my judgement or criticisms. One of the purposes of this work has been to empathetically speak with radical young people in order to better understand them. Through these interviews, I attempted to identify certain nodes within social media networks (such as content creators, videos, books, memes, etc) that influence their ideology and worldviews. If we are hopeful to persuade people, and ultimately to change their minds, we should first know how they shift and develop in their ideas. This research is a prerequisite to any narrative intervention that can be made later.

Amber A’Lee Frost, friend of the pod, recently wrote a piece in Jacobin that discusses this work in detail: Gen Z is Super Weird.

No one I have interviewed has ever been doxed or identified. This guarantee of anonymity allows people to speak candidly and to represent their views honestly.

In the podcast series My Political Journey, we explore the media influences, content creators and communities that shape young people’s political ideas.

In the written series 20 Interviews, we explore fringe political imaginaries and dystopian or utopian futures.

Today, liberal democracy feels very uncertain. Ideology is back and history is moving once again. As fewer people are able to access the benefits of the mainstream, citizens naturally move towards the further edges of the political spectrum and seek new solutions.

At the bottom of these “disinformation” and “post-truth” rabbit holes, the only clarity to be found is that everything is ideological. Ideology creates self-validating and mutually exclusive frameworks for understanding the world. Disinformation is itself an ideological statement that begs the question; who is the arbiter of this truth? Social media has helped to fracture our consensus of “the center” but this is only one piece in a long arc of cultural, economic and historical narratives that are now all coming to a head. Soon, “the center” will be realigned by a hard break to the left or right.

This younger generation, on the whole, feels a great uncertainty looking forward. The pervasive sense that you are living in a society whose best days are behind it, tends to point your political imagination toward dark places. In particular, young people turn to social media for answers. Exploring deep online spaces is a constant process of reprogramming. The cumulative effect is like something out of a CIA black site manual for inducing psychological stress. Everyone questions everything until they are ultimately forced to choose a side. In the past few years, I’ve watched hundreds of young people shift from irony to ideology and subsequently cross over between many various sets of beliefs.

In 20 Interviews, when I asked my subjects, “Who *you* are in this society?” Most answers came back as “another face in the crowd”, “another average joe” or “just a regular guy”. Maybe this is humility or maybe it’s pessimism. But I think when you compare these responses against the more common millennial aspirations of being a creative director or becoming a famous influencer, it begins to frame out a broader generational understanding that it is beyond the ability of any one individual to determine their own fate. This emergent collectivity may grow to become socialism, or to become fascism, but it seems unlikely that our old brand of political individualism will remain intact for long.

In the last few years there has been a lot of talk about the need to deradicalize young people from the far right. And while these efforts are of course urgent and necessary, less resources have been dedicated to the question of: deradicalizing them back into what? Reining in young people to put us back on the path toward imminent climate catastrophe and increasingly brutal iterations of techno-capitalism is just bailing water out of an already sinking global ship. The truth is that today is indeed a time for radical politics, just not from the far right.

During this research, I forged unexpected friendships with many of my subjects, some of whom I am still in touch with today. I later became an advisor for the high school senior project from the young man interviewed below. For another person, I wrote a letter of recommendation on their college application (they got in). Several other interviewees have since written and published their work on

.It has been a deeply rewarding and powerful experience to have know these people for almost 8 years and to watch them grow in their beliefs, worldviews and personal lives. This was not at all what I expected when I began these projects. But, in hindsight, they have become some of the most meaningful experiences of my life.

Leftcom Internationalism

My guest is a 16 year old communist. For several years this account was a potent micro-influencer, prolific essay writer, and agenda setter for young online communities. He was also a notorious troll whose antics acculmulated a highly dedicated following. Soon after, many of these users made contact with a real world organization on the internationalist left. We will explore this in an upcoming episode of:

In particular, this interview gripped my hopeful political imagination and inspired an artwork that envisions this future scenario at a life-size scale. The subject describes a post-climate collapse society in which workers self-organize to repurpose the urban towers of global finance and convert them into vertical farms.

Framed as a vertical TikTok video, we see an anarcho-communist, dressed appropriately in red and black, taking a break during their agricultural labor shift. A skycraper in the Bay Area of San Francisco has been transformed into a collective farm. Pulley systems link similar grow stations across a network of buildings. In this society, energy consumption is kept to a minimum, save for the absolute necessity of raising crops. Our subject reads an early ecologically-minded text by Amadeo Bordiga, leader of the anti-Stalinist Italian left, entitled The Human Species and the Earth’s Crust, which explores the unsustainable nature of cities and their incompatibility with socialism.

If the last few years have taught us anything, online aesthetics are a potent and meaningful force in society. From presidential campaigns like Brat, to the weekly newscycle of Luigi-posting, memes have completely rewired today’s political discourse. Our institutions may be crumbling and illegitimate but the possibility exists that art could once again become an influential force within culture. I hope we can harness this potential towards a brighter vision of the near future.

I think art is already back on its way up. Purely anecdotal, but just yesterday I overheard a kid saying to his ma something that roughly translates to; I like paintings but not museums. The mother of course found this very strange, but I think the kid was on to something.

I like memes, but not the platforms. Yet, making a platform that encourages the creation of meaningful art has to be possible. While most content is mostly meant to catch attention. There is also a lot of work made to provoke thought.

I find that, despite their shortcomings, message-boards are currently one of the better places for facilitating memes that provoke thought because there is no algorhitmic incentive to optimize for other things: watch length, likes etc.

On messageboards, people download the pictures that enter their conscious the most, and thus the most "impactful", pictures tend to proliferate. Remembering and posting such a picture later requires more effort than merely pushing a like button, or even worse, affirming by contuing to passively consume content i.e., doomscrolling. Because of this minuscule effort required there is a filter against passive affirmation, against auto-pilot sharing of content that barely enters the persons conscious.

how did you define doxxing in this work?