This week’s newsletter comes from my recent talk at MoMA for an event titled The Aquatic Brain, organized by Carson Chan and Matthew Wagstaffe of the Ambasz Institute. I explore the work of media theorist Vilem Flusser in contrast with Jordan Peterson’s infamous lobster hierarchy. We take a creepy Lovecraftian tour through evolutionary design to learn some lessons about our own human society.

This interdisciplinary lecture series is part of the program for “Good Night Good Morning”, a survey exhibition of 50+ years of work by canonical artist Joan Jonas.

A reminder: this newsletter is fully supported by paying subscribers. Your support allows me the time to write, research and publish. If you like these topics, appreciate the perspective or find yourself mildly entertained by this material — consider becoming a paid subscriber this month or get a discount for the full year:

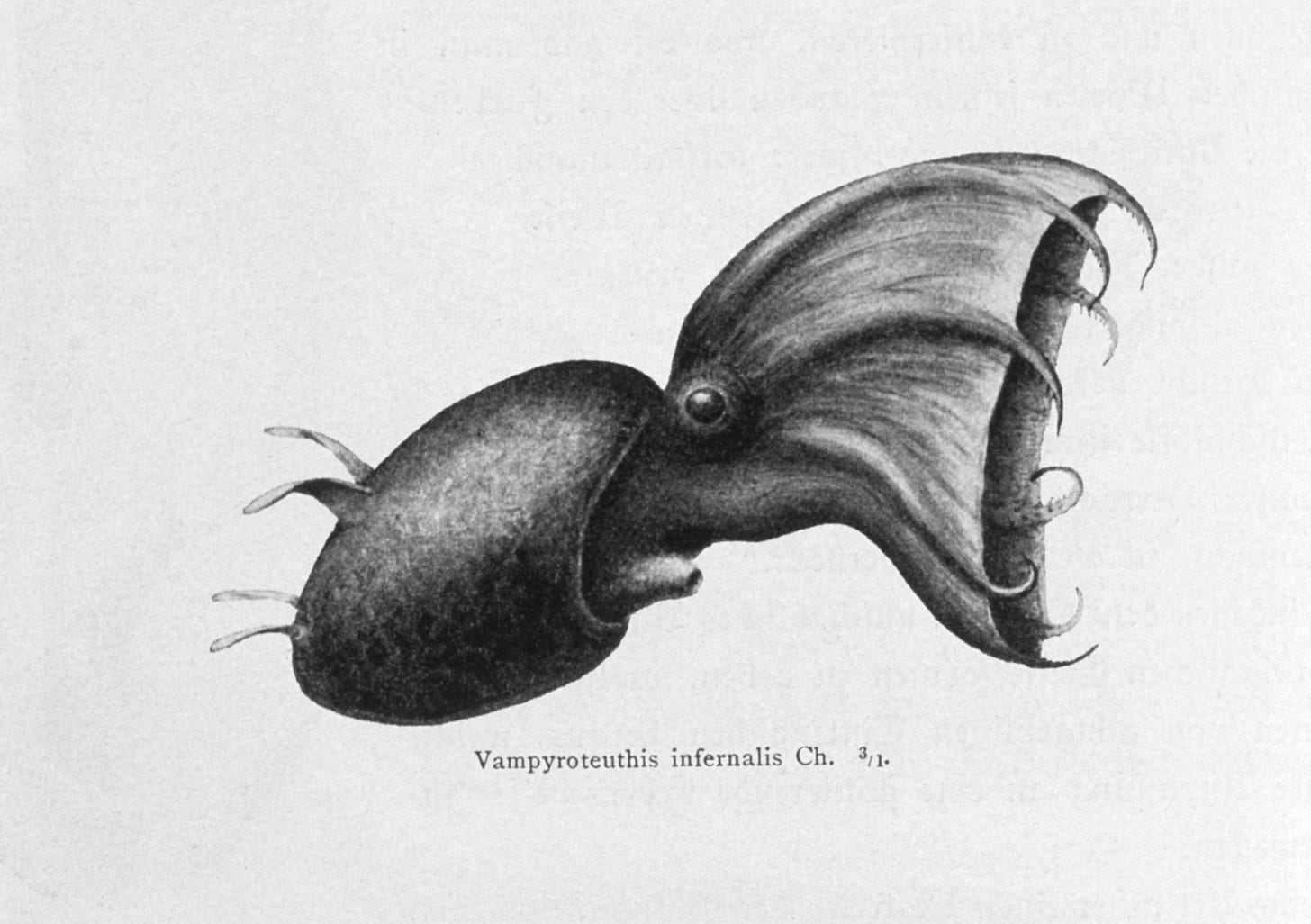

The Vampire Squid from Hell 🦑

Vampyroteuthis Infernalis is a lesser known book by media theorist Vilem Flusser. It was originally published in German in 1987. Flusser’s text is masterful exploration of phylogenetic horror exploring the philosophy of design and evolution.

Vilem Flusser is an increasingly influential media theorist. He is Czech by descent. He spent most of his career in Sao Paulo, Brazil. He was a columnist for ArtForum in the 90’s. His vast body of work includes writings in German, Portuguese and English.

In 2011, the first English translation of his seminal text Into the Universe of Technical Images was published by the University of Minnesota Press. A few months later, artist and writer Chris Wiley, discussed Flusser’s better known work Towards a Philosophy of Photography in an article titled “Depth of Focus” in Frieze Magazine.

These texts by Flusser, originally written in 1984 and 1985, offered a newly relevant map to our increasingly complex digital world. They arrived just in time for social media to take off and transform our global communications networks and society along with it.

The timing of the English translation in 2011 is significant, because many of my artist peers graduated shortly before then (myself in 2010). Flusser was not included in the media theory canon taught to us, but young artists of the post-internet milieu embraced these texts as a map to our new technological moment.

While Flusser’s impact on the field of media studies has profoundly grown within the last decade, his work addresses a wide array of other fields, including design, philosophy, politics, and most relevant to today: evolution.

Vampyroteuthis Infernalis is a 1987 book by Vilem Flusser and artist Louis Bec, first published in English in 2012, (again by the University Of Minnesota Press). Its title refers to what was at the time, a little known and rarely studied species of “vampire squid” that lives in the deep recesses of the ocean.

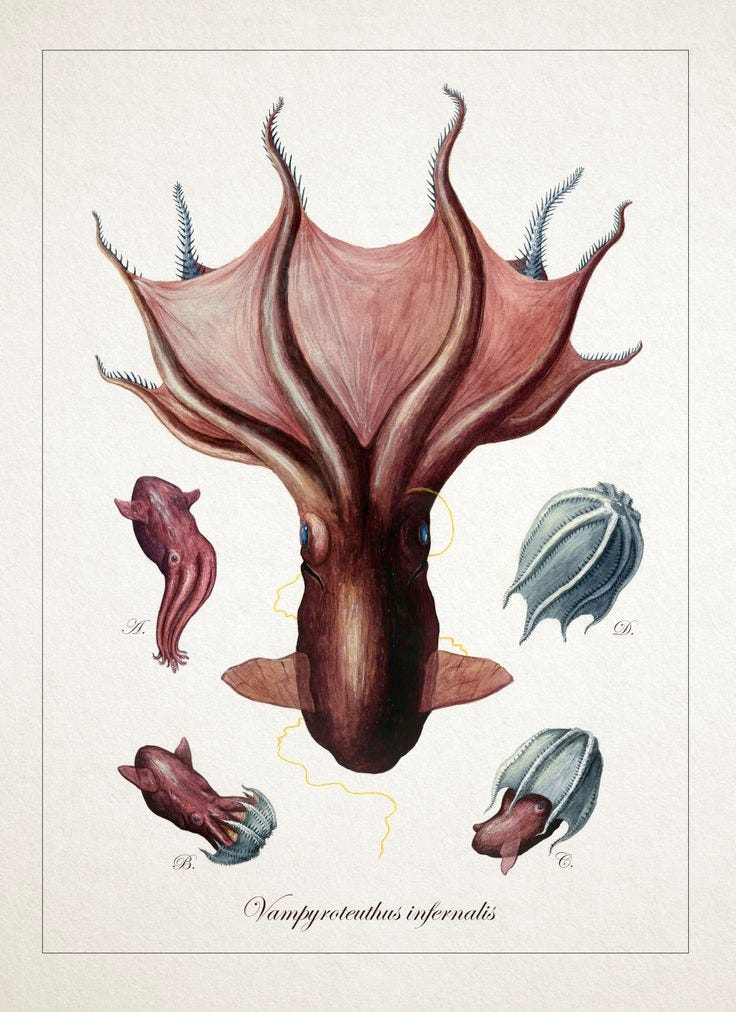

The Vampyroteuthis Infernalis are highly elusive and prone to suicide when held in captivity. As a result, very little was known about them, especially during the writing of this text some 30 years ago. They are highly intelligent, ruthless predators and often cannibals. Earning them the colloquial nickname “the vampire squid from hell”.

When you meet another Flusser scholar, you are most often talking about his media and design work. Vampyroteuthis Infernalis is by far his most challenging and weirdest text. (It's very, very weird.) He eclectically borrows from Kant, Plato, Heidegger and Marx. As well as from both Darwin and Lamarck. Flusser’s book is, as he describes it, more of a fable than a scientific treatise. When I first read the text, over ten years ago, I mistakenly assumed that he had created a fictitious or mythological creature. Imagine my surprise, and horror, when I later learned that it was indeed real.

Flusser examines the Vampire squid from the perspective of the human and the human from the perspective of the Vampire Squid. His philosophical argument is that our species represent dialectical opposites.

Both of us have taken radically divergent evolutionary paths. Humans inhabit the earth's crust, surrounded by air and illuminated by sunlight. The Vampire Squid lives in the low oxygen recesses of earth’s oceans, a habitat devoid of all light, save for its own bioluminesce. The immense pressure of its environment, many hundreds fold greater than our own atmosphere, would make it impossible for either of us to survive if we swapped places. In Flusser’s time, no human had ever laid eyes on a living Vampire Squid. They were studied from fossils, or very rarely when an intact corpse would float all the way up to the ocean’s surface.

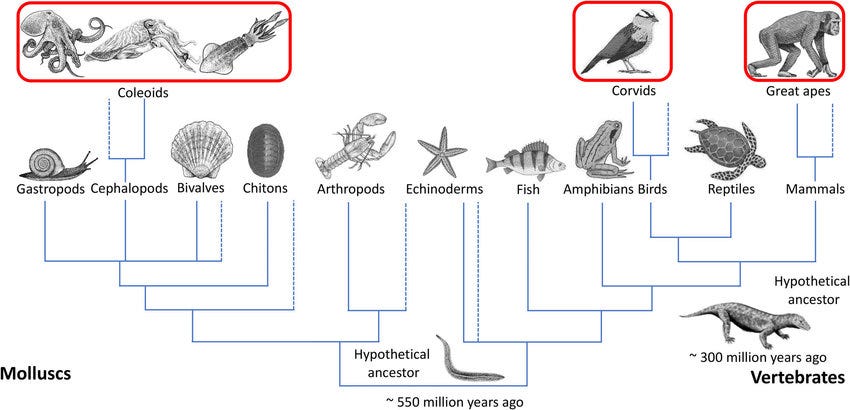

The common ancestor between humans and the Vampire Squid is a primitive flatworm. It was found on the beach between sea and land, stretching back over 600 million years, before the animal kingdom diverged into two groups of organisms – those with backbones and those without. While each species dwells upon the same planet, humans and cephalopods are as different as they come. It is perhaps as close as we can get to studying extraterrestrial life here on earth.

As Flusser diligently traces in his book, the evolutionary path of the vampire squid involves a rotation of the body and its digestive tract. Its brain encircles its esophagus. The control centers of its nervous system are distributed throughout its body. The term “Cephalopod” comes from the Greek; Head-Foot; “cephalo-pod”, as if to say that the being is standing on its head. Humans might be thought of as facing forwards, while cephalopods face in reverse.

As one reads Flusser’s meticulously detailed descriptions of this radically different body, we cannot help but imagine our own form being violently stretched and contorted by deep time. Vampyroteuthis Infernalis reads as both a scientific study and a gruesome tale of body horror. Put simply, we are two forms of life that represent each other's opposites, both literally and metaphorically.

Yet what we learn in the study of these unique animals also reveals much about ourselves. In a profound example of convergent evolution, we both have photographic eyes, light sensitive cells that are phylogenetically unrelated. This is at the core of Flusser’s interest; a determinism on the level of design and evolution, where the development of life and intelligence can be understood as a byproduct of the material world.

The emergence of cephalopod intelligence, the development of its unique brain and nervous system, all give us insight into our own faculties and how we understand the world. These comparisons are of particular relevance today, on the threshold of AI, as they challenge definitional frameworks of what intelligence even is. (Listen to my episode with Benjamin Bratton on this very topic.)

As Flusser writes, “what we [humans] call ‘evolution’ is, essentially, the tendency of life toward socialization.” He begins with the organization of cells into complex structures and hierarchies. And reads this out further to include super organisms, such as ant colonies, or even, human societies themselves.

Comparing human social life to that of the vampire squid, Flusser writes;

“All of our political activity is directed against our biological condition, against predetermined inequalities. The difference is that our inequalities also have a large and overlying cultural component. Our political struggles are thus against this cultural superstructure, which we strive to rebuild. Moreover, we are able to imagine cultural structures, or “Utopias”, in which even our biological constraints are done away with. The Vampyroteuthis cannot fathom Utopias, for the structure of its society is not a cultural product but rather a biological given.”

“For us, political activity is a question of freedom that poses itself dialectically: as the self-assertion of an individual within society, and as the individual acknowledgement of other humans. For the Vampyroteuthis there is no dialectic of political freedom. It is biologically necessitated to recognize the hierarchical rank of its brother, and it can only become free if it disposes of this necessity. For it, then, freedom is cannibalism, the right to devour its kin.”

Flusser’s collapsing of what Stanislaw Lem might call geological history, down the scale of social history, may seem incongruent. But this conflation of time scales is also the determining feature of our epoch; the Anthropocene. Our world is now being shaped by the carbon emissions of human life, in its current method of social organization, and effecting planetary changes on a geological scale, best encapsulated in the term “man-made climate change”. Ironically, the development of intelligence on this planet is both the cause of global warming as well as our best hope for a solution.

Surprisingly, Flusser’s framing of social organization as a downstream result of evolution, may sound reminiscent of ideas that are increasingly popular online today. Characters among the “Intellectual Dark Web” and its extended universe will argue that all of human social life is predicated on ruthless domination, evolutionary psychology and sexual reproduction. (Think of Jordan Peterson’s infamous lobster dominance heirarchy). This school of thought views all political and social structures as the product of deep seated biological drives.

But Flusser’s evolutionary and material determinism proposes an entirely separate view. He argues that humanity’s deep seated nature is progress towards “ever greater levels of socialization” in which human intelligence struggles against purely biological hierarchies. He goes as far as to describe the Vampire Squid’s society as “a hate movement”. (That’s a real quote on page 59.)

Flusser writes;

“the Vampyroteuthis stands on its head: it's hell is our heaven, it's heaven our hell. For us, its murderous and suicidal anarchy would be an infernal society, and yet, to it, such anarchy represents an inaccessible heaven. Love and socialist collaboration and cohabitation represent, to us, an inaccessible and heavenly Utopia. Yet there is something of the Vampyroteuthis in each of us.”

In the Vampire Squid we behold our own inverted reflection. Utopia, the possibility of imagining a better world, is the defining feature of our species and as Flusser suggests, perhaps also our evolutionary destiny?

“Ironically, the development of intelligence on this planet is both the cause of global warming as well as our best hope for a solution.” Is it intelligence, in general, that is the hope? As a general development, it seems more like a cancer; infestation, or addiction—some out of control process that like, say, obesity or overpopulation won’t be solved by more of the same. Maybe we could consider intelligence in evolutionary terms; in which case, what intelligence could we develop that would make us have perspective and awareness of our limitations?

Thank you for writing this! such a fascinating and scintillating read!