If these online communities are unfamiliar, this may be a useful primer: Politigram & the Post-left. This text was originally published on

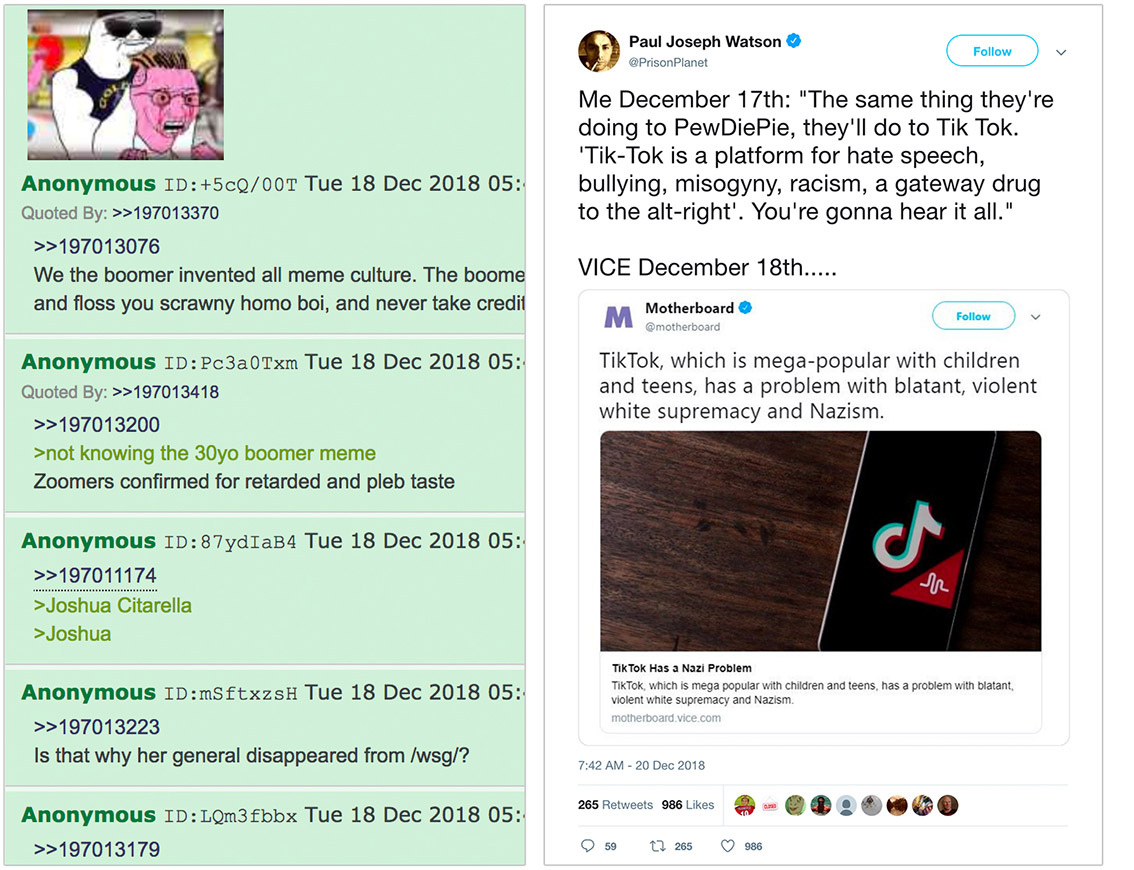

Near the end of 2018, I wrote an article about TikTok and Gen Z. My piece focused on generational differences in social media use. I argued that, broadly speaking, Millennials are individualist, entrepreneurial, and focused on a personal brand while Gen-Zers are collectivist, nihilistic, and interested in identity play. A few weeks later, InfoWars’ Paul Joseph Watson made a video, The Cultural Significance of TikTok, which awkwardly retrofits my text as a seeming endorsement of his right-wing agenda. Watson describes TikTok as a cultural battleground in which Gen-Z rebels against the overreach of Millennials’ political correctness. [1] Today, the video has 1,200,000+ views on YouTube. There are several versions circulating online. It’s also become a topic in its own right, sparking threads on various right-wing message boards including 4chan’s /pol/. A roast appeared on the satirical news website NPC Daily.

To be sure, numerous publications released articles about TikTok when it was trending on the App Store late last fall. Some writers mentioned concerns about offensive content and hate speech. Just about everyone was shocked to see how young TikTok’s user base is. The media’s response quickly came to a head with a VICE Motherboard article bearing the outrageous headline "TikTok Has a Nazi Problem," spawning further replies by conservative YouTuber Sargon of Akkad, among others. For the space of a few days, TikTok was a front line in America’s ongoing culture war.

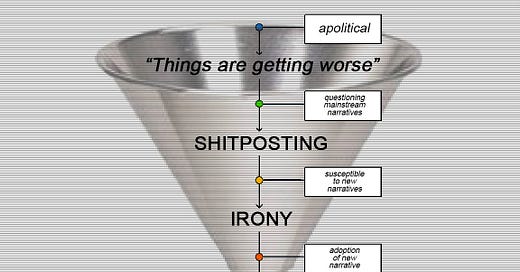

History shows that reactionary politics, especially among young people, flourish in times of declining wealth and labor market prospects. In observing the online content teenagers produce, we can see that Gen Z has learned to expect less than earlier generations. Given that real wages have been stagnant for nearly forty years, life expectancy is declining, and the environment is collapsing, this makes sense. Things are getting worse. The burgeoning youth conservative movement and the generational realignment Watson proposes stand as strong evidence for the need for a materialist Left.

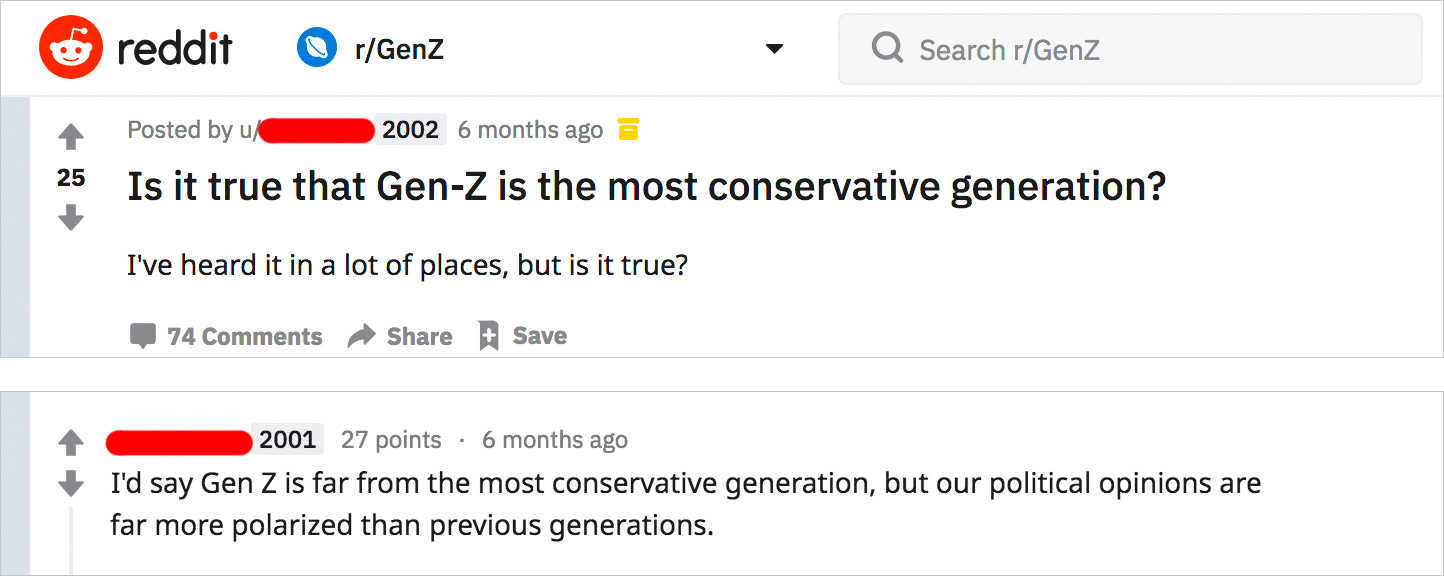

Gen Z’s online activity suggests that many in this age cohort do hold conservative values (or at least enjoy the identity play of a conservative position within our current media landscape). But it must be noted that Gen Z also includes a rapidly growing progressive movement. Across all spheres of American society, the center is failing. As fewer people are able to access the benefits of the mainstream, alternative narratives have begun to flourish and citizens move further toward the polarized edges of the political spectrum.

Irony and Capitalist Realism

Americans born after the era of Reagan and Thatcher inherited a world where multiple radical projects had recently failed or been popularly discredited. Centralized states like the USSR had collapsed, the communes of the '60s-'70s had long-since been deserted and seemingly all revolutionary potential had been dissolved into a system of global capitalism. We couldn’t restructure society but neither could we opt out. The vast archive of the internet effectively flattened the past and contributed to the pervasive feeling that we were indeed living at the “end of history.” [2] This shift away from historical perspective helped to foreclose our political imaginations and was celebrated by the capitalist doctrine as “the end of ideology” and end of class struggle overall. [3]

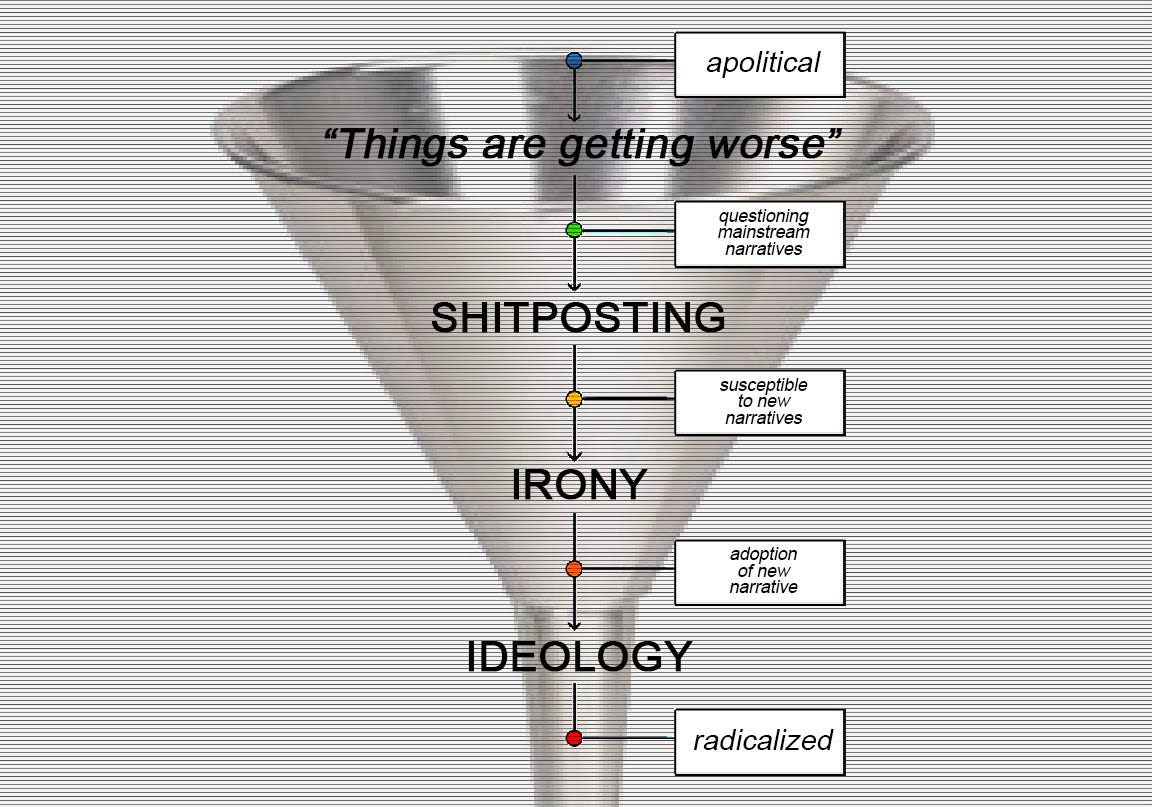

To insulate ourselves from these seemingly guaranteed failures, Millennials, and Gen Z after us, adopted irony as a cultural strategy. Irony allowed us to continue life under late capitalism while psychologically sheltering ourselves from the demoralizing reality. Irony as culture became: “The band I like will inevitably sell out, so I might as well buy-in early.” Irony as politics became: “The movement will inevitably be corrupted, so I might as well side with capital.” Ultimately, it was okay that a project failed because irony allowed us to maintain the plausible deniability that we “never really liked it to begin with.” Why resist, if alternatives are impossible?

In the mid-00s (or when Millennials were the age that Gen Z is now), the mainstream was wearing ironic T-shirts of bands they didn’t like. The enthusiasm may have been insincere but it was paid for in real dollars. This disingenuous mode of consumption was the first breach between the world of ironic aesthetics and social reality. Soon, irony didn’t so much signal active engagement as it suggested an underlying political nihilism, allowing one to disassociate from the real world effects of one’s own actions. The inertia of ironic consumption and production continued to accelerate right up until 2016—at which point the Pepe-style trolls of the Alt-right made it clear that irony had never been apolitical. Ironic propaganda functions the same as real propaganda. Ironic voting is just voting.

Irony after 2016

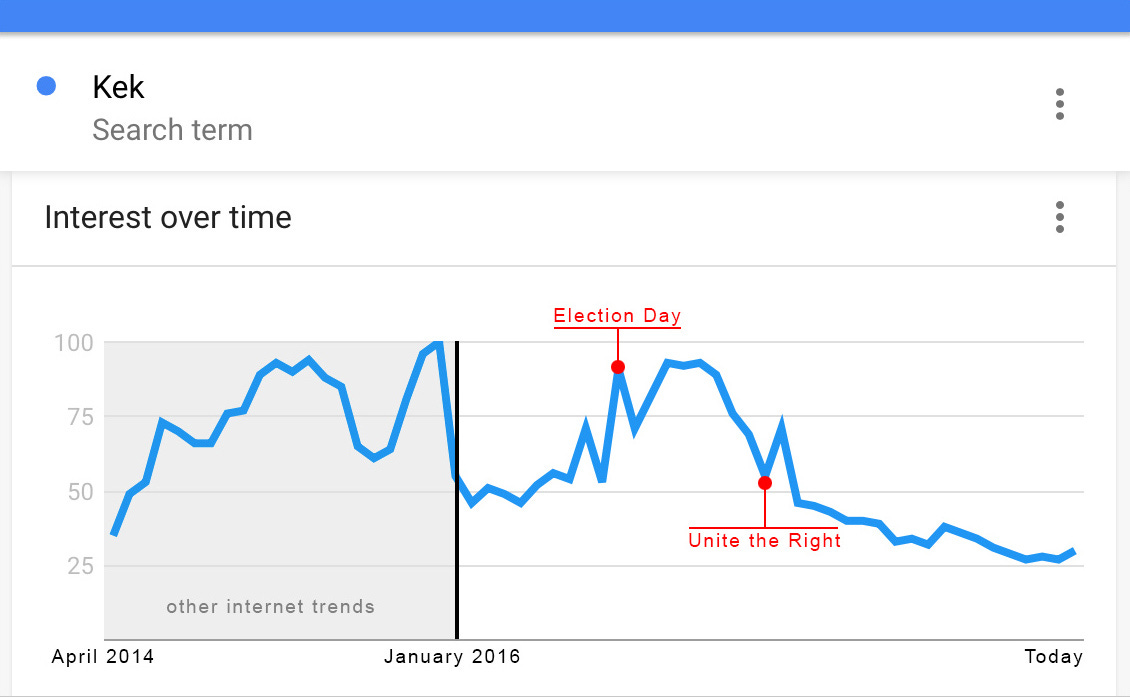

The past few years online have been a disastrous field test for the political efficacy of irony. The Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, VA, (August 2017) proved to be a watershed moment for the racist trolls of 2016. As the IRL events played out, 4channers were physically pushed out of white nationalist demonstrations. And once it became ‘real,’ most of the Pepe kids called it quits. Almost overnight, the Barrens Chat aspect of the Alt-right disappeared. Those that remained had become hardened ethno-nationalists who felt no need to cloak their message in irony.

After Charlottesville, conservative culture warriors like Watson and Sargon—wary of moral culpability and deplatforming—quickly tried to distance themselves from the Alt-right. Today, their worldview and careers hinge on the fuzzy distinction between rhetorically libertarian positions (which may contain implicit references to white identity) vs. the explicit racist agenda of the new online Right. Self-preservation precludes them from recognizing how their audience may serve as an incubator for further radicalization.

As TikTok is still a largely ‘normie’ and tightly moderated platform, it has become a tactically useful talking point for alternative social media stars (and gamer celebrities like PewDiePie). So long as TikTok can float in the limbo of irony, these culture warriors will defend it. Losing this battle would be admitting defeat on the greater front.

Gradients of Politicization

In the fall of 2018, I, like most observers, believed that the mass appeal of edgy trolling had come to an end. I was therefore surprised to see a style qualitatively similar to the early-2016 use of Pepe emerge on TikTok.

I want to be clear that TikTok trolling culture is distinctly different from the troll culture of 4chan. TikTok troll content is produced for a wide and nondescript online audience while 4chan trolls primarily use misanthropic in-jokes which signal back to their own niche community. While TikTok’s troll content is offensive and outrageous, it does not, thus far, resemble the targeted harassment campaigns of the Alt-right. TikTok trolls are mad at the world and criticize the abstract phantom of “libtards” but they do not (yet) have intent to cause suffering for specific individuals. A public video making fun of someone is acceptable but a barrage of private messages is not. This distinction is important because it reveals an underlying difference in the individual motivations for these two groups and will impact effective policy prescriptions.

To further analyze the content Gen Z produces on TikTok and other platforms, I want to propose a framework within which we might classify it along gradients of politicization. These specific terms and their definitions have been tactically muddied by the Right but the general arc of progression remains clear.

Shitposting Doesn't Scale

Before the context collapse of large scale networks, [4] shitposting performed an important social function within small scale message boards. Within these communities, indeterminacy was essential to the process of meaning making. Shitposting was a way of proposing ideas that existed potentially outside the bounds of the Overton window and whose delineation helped to define the moral and ethical codes of the collective. Often uncertain of what they themselves believed, users would push an idea to its hyperbolic extreme in an attempt to find their group’s collective limit. Once breaching the consensus codes within their community, they would privately scale back to calibrate where they in fact stood on the issue.

This process worked reasonably well on gaming forums in 1999. Not so much today. Perhaps this style most appropriately tracks onto small scale networks like group DMs. Shitposting is also a way of re-asserting individual freedom within online collectivities. The power of any one individual to derail a thread reaffirms the autonomy of all individuals within the group and subsequently gives value to the instances where users do cooperate.

Virtue Signaling to the Right

Clearly, many TikToks are cut and dry examples of racism or misogyny, often internalized. Content like this is not altogether surprising as the videos are produced by and for a mostly white audience of transgressive teenagers. Yet to dismiss these videos entirely risks losing an important insight about the younger generation and the emergent cultural forces now shaping our political reality.

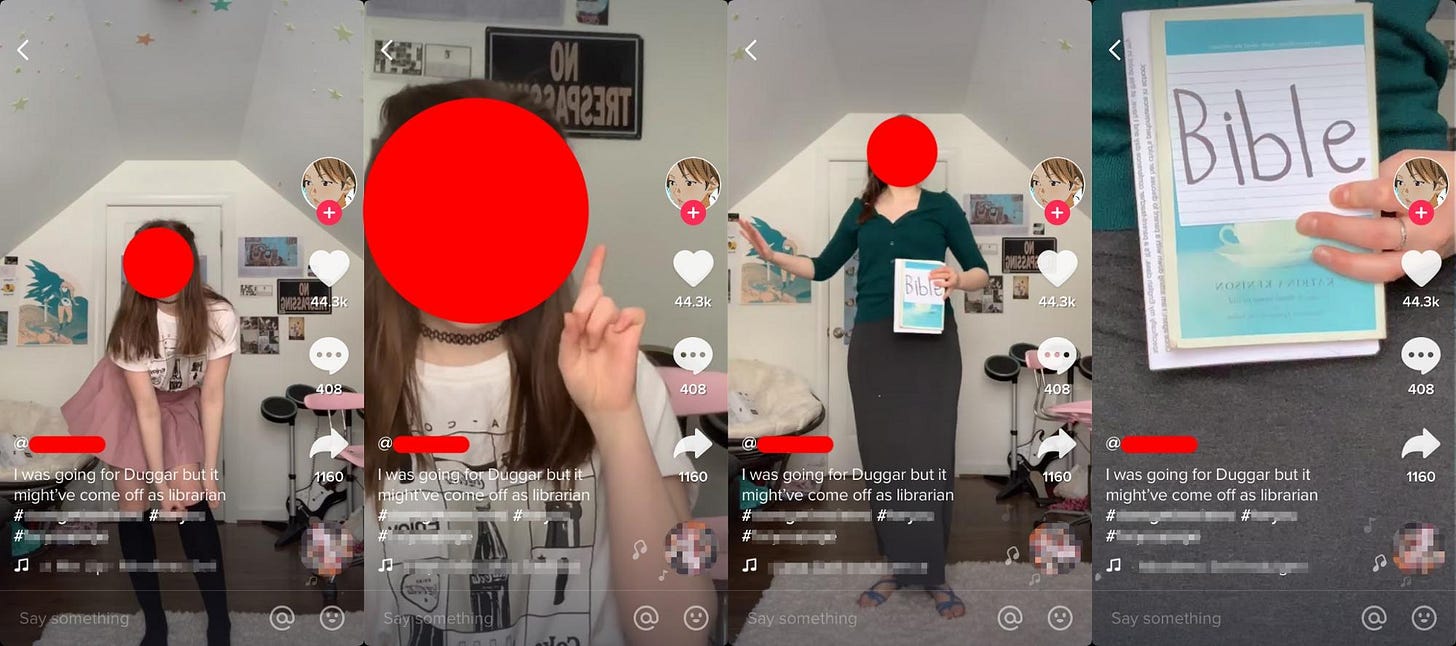

We should take notice that the overwhelming majority of edgy teens on TikTok are not living out the ideology they profess online. Themes of gender inequality have worked their way into most every meme format on the platform. Yet despite the popularity of videos where young women describe themselves as “property” or voluntarily “go back to the kitchen,” these users are not actualizing their “Trad Lyfe” values. The re-emergence of so-called Christian conservatism doesn’t seem to result in any increase in church attendance. Instead, they seem to be spending most of their time making antagonistic memes on social media. Further exploring these users’ pages reveals the abundance of ideological inconsistencies one might expect from contrarian teenagers: One video appears superficially racist, yet the next video shows them mocking police officers and, further down, we see them collaborating in duets with transgender users. The online content teens produce is a slurry of zeitgeist issues about which they themselves may not yet know what they truly believe.

If young people are advocating for a return to conservative values in their online posts but not in their actions, we must ask: Why are young people virtue signaling toward the Right? Underlying the emergence of youth reactionary culture is the glaring failure of neoliberal capitalism to deliver on its promises. Young Americans will face the worst economic odds of any post-war generation. Life expectancy continues to drop (most dramatically in Red states). [5] Teenagers cannot identify the causes of this general decline but they have already internalized its downward trajectory. Their grandparents’ single-earner income provided for a four person household. Their parents’ same family unit now struggles to reproduce its standing with two earners in the workforce. Just a few years ahead of them, Millennials with multiple roommates all tweet about the perils of student debt and freelance precarity. These material conditions, combined with the real existential threat of climate change, make Gen Z acutely aware that they are living at the end of an era; that they were born on the other side of the so-called “end of history.”

Since teenagers rarely have much interaction with government, they tend to understand platforms, the media, and even the entertainment industry as a single homogenous ruling order. Reinforcing this is the fact that many came into their early adult awareness during Obama’s presidency, a time when Democrats, the media class, and tech platforms were seemingly immutable allies. For many in Gen-Z, this perception has crystalized into a progressive neoliberal establishment toward which they now direct all of their frustrations. Young people’s lack of historical awareness and well founded anxieties about the future make them especially vulnerable to the charlatan tactics of right-wing culture warriors. As the failures of neoliberalism become clear, young people attempt to distance themselves from the culture that they, in some ways correctly, understand to have robbed them of their future. TikTok trolling is a backlash to diminishing expectations in American life.

The Shared Grievance

This understanding of Gen Z's worldview and leanings is not speculative. Their everyday posts are literally an itemized list of grievances in plain, uncloaked language and these core complaints are nearly unanimous across all corners of the political spectrum.

While today teenagers tend to be seen by Western culture as dependents, not yet fit for war, politics, or work, it is worth noting that most revolutions, historically, have been led by young people. Teens are becoming politicized because they have been handed a world in crisis.

The lesson of the heterodox right is clear, the center is failing. For many of us on the Left, the blame rests with the Democratic Party who, over the past few decades, has de-emphasized its support of labor issues while doubling down on financial deregulation and technocratic solutioneering. [6] For young people in a political landscape whose only options are a dead-end future or a return to brutal hierarchies of the past, there is, as right-wing influencers will tell them, seemingly no choice. Reactionary politics flourish most when it is difficult to imagine a better future.

1 Paul Jospeh Watson commented, "Gen Z is a natural, evolutionary, self-correcting antibody to the Millennial pathogen that has infected our culture." "The Cultural Significance of TikTok" (YouTube, Dec. 17, 2018)

2 Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” The National Interest (1989)

3 Fredric Jameson, “An American Utopia: Dual Power and the Universal Army” (2016)

4 Also see: Poe's Law

5 It may not be possible to gather definitive data but my strong inclination, which is shared by other researchers in the field, is that the majority of these teen users live in conservative districts.

6 Thomas Frank's Listen, Liberal: Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People? (Picador, 2016) is probably the best read about this recent history.